As antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) are phased out, animal nutrition strategies must increasingly rely on natural ways to support gut function, animal resilience, and performance. In fact, one of the most powerful yet underutilized tools in this toolbox is dietary fiber. Although once seen as an anti-nutritional factor, fiber is now recognized for its vital role in gastrointestinal (GI) health, especially in monogastric animals like pigs and poultry. From regulating intestinal motility and supporting the gut lining to feeding beneficial microbes, fiber is essential – but only when understood and applied correctly.

Understanding dietary fiber: What it is and what it does

The term dietary fiber (DF) was first introduced by Hipsley in 1953 to describe non-digestible components of plant cell walls. Since then, the definition has evolved to emphasize the physiological effects of fiber. Today, DF is defined as carbohydrates indigestible by endogenous animal enzymes.

Broadly, DF includes cell wall compounds such as cellulose, hemicelluloses, mixed linked β-glucan, pectins, gums, and mucilages. Lignin, a complex phenolic compound in plant cell walls, is also classified as DF because it affects digestibility.

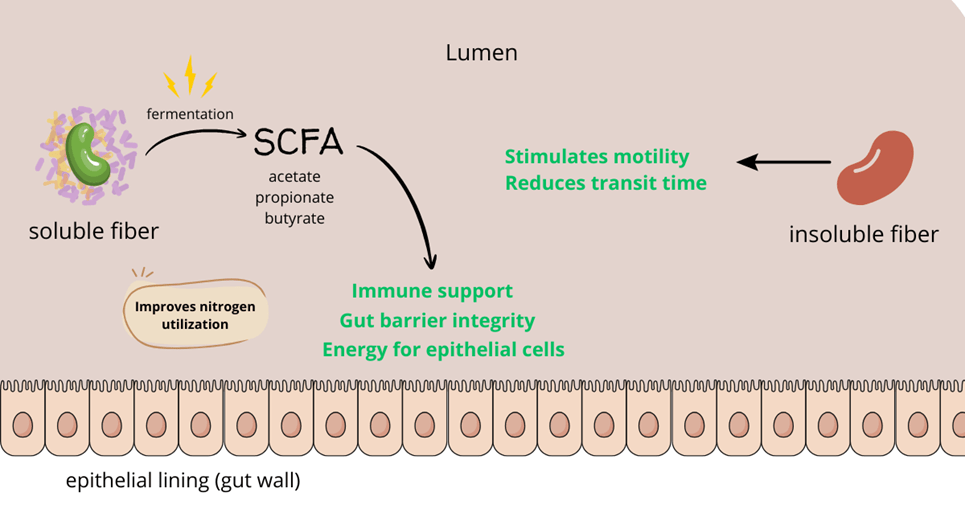

From a physiological standpoint, the soluble fraction of DF comprises non-starch polysaccharides (NSP), non-digestible oligosaccharides, and resistant starch (RS). Consequently, these components resist enzymatic hydrolysis and serve as substrates for microbial fermentation in the intestine, producing beneficial effects. Importantly, fermentability is not strictly tied to solubility. Some insoluble fibers (e.g., lignocellulose or finely ground hemicellulose) can be partially fermented and contribute to short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production.

Fiber fermentation and its primary utilization pathways

Soluble and fermentable fibers are metabolized by gut microbiota, producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that serve as a major energy source for epithelial cells, particularly in the large intestine. Furthermore, these SCFAs help maintain gut barrier integrity and support local immune functions. Fermentation also contributes to nitrogen balance in the gut. Insoluble fibers, on the other hand, stimulate gut motility and reduce transit time.

The structure and solubility of dietary fiber significantly affect its fermentability. Soluble fibers, which dissolve in water and increase viscosity, are fermented more rapidly than insoluble fibers. Highly branched fibers offer more surface area for microbial enzymes and degrade faster, while linear fibers like high-amylose starch ferment slowly. Additionally, chemical modifications (e.g., cross-linking or esterification) can hinder fiber degradation.

How fiber strengthens the intestinal barrier

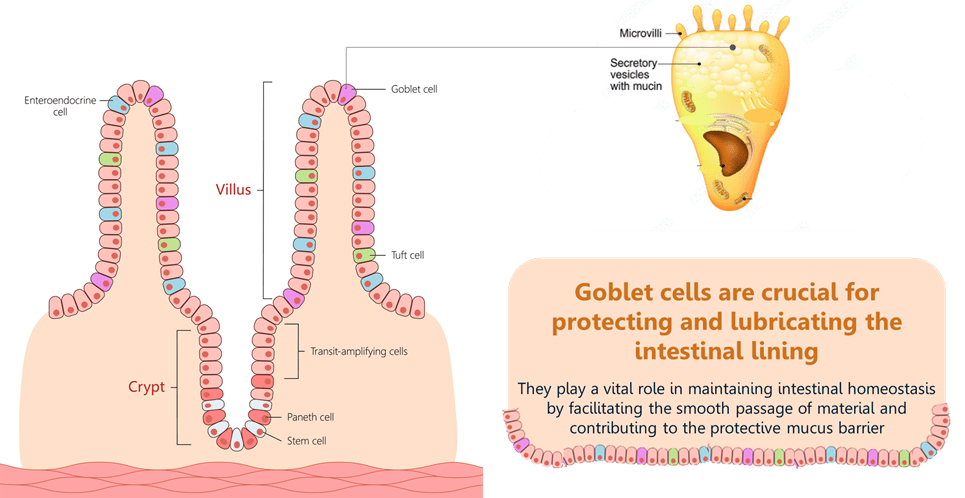

Fiber plays a central role in intestinal mucosal development. In fact, through fermentation, SCFA like butyrate fuel epithelial cells, enhance mucin secretion from goblet cells, and strengthen the gut barrier. As a result, this enhanced barrier function makes it more difficult for pathogens to invade and helps reduce intestinal inflammation.

In young animals, especially post-weaning piglets and chicks, moderate levels of dietary fiber can also promote gut tissue development. Specifically, this includes increases in villus height and reduction in crypt depth, which are key to improving nutrient absorption and immune readiness (Wang et al., 2020).

Microbiota matters: feeding the right microbes

The gut is home to a vast community of microbes, which rely heavily on fermentable fiber as fuel. In return, they produce beneficial SCFA, thereby suppressing pathogens, and at the same time communicating with the host’s immune system.

The presence of functional fiber maintains microbial balance and promotes key species like Lactobacillus, Faecalibacteriuma prausnitzii, and Bifidobacterium. However, without enough fiber, microbes begin degrading the gut’s own mucus lining – a state that compromises barrier function and invites disease.

As the livestock industry moves beyond antibiotics, dietary fiber has become a cornerstone of natural gut balance strategies. Once dismissed as an anti-nutrient, fiber now stands as a vital component for maintaining intestinal function, microbial balance, and overall animal performance.

At Hankkija, the understanding of functional fiber has led to the creation of ProHumi® – natural, science-based feed material for monogastric animals. Containing prebiotic fiber and humic acids, it has proven effects in pigs and poultry, supporting gut balance and stable performance.

Contact our sales to discover how ProHumi® can strengthen your feeding strategies and deliver proven results in your production

References

- Jha, R. & Berrocoso, J.F.D. (2015). Dietary fiber utilization in swine. Animal Nutrition, 1(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2015.03.002

- Jha, R., Fouhse, J.M., Tiwari, U.P., Li, L., & Willing, B.P. (2019). Dietary fiber and intestinal health of monogastric animals. Front. Vet. Sci., 6, 48 https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00048

- Wang, M. et al. (2020). Villus height and growth performance in weaned piglets. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr.https://doi.org/10.1111/jpn.13299

Jin, L & Reynolds, Lawrence & Redmer, DA & Caton, Joel & Crenshaw, Joe. (1994). Effects of dietary fiber on intestinal growth, cell proliferation, and morphology in growing pigs. Journal of animal science. 72. 2270-8